The sibling founders of Matteau Swim, a three-year-old Australian fashion label, are on opposite sides of the globe.

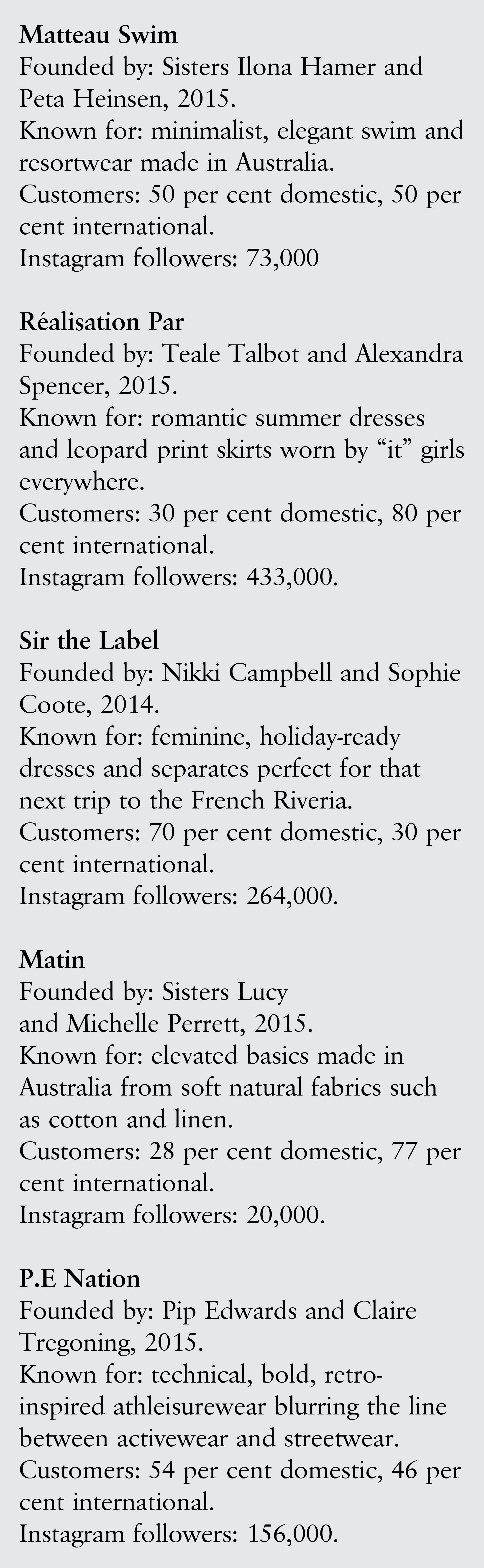

Australian Fashion’s New World Order

Young, savvy Australian labels are dispensing with traditional retail stepping stones in favour of a direct-to-consumer model and immediate access to billions of potential customers. The meteoric success they’re achieving is completely unprecedented – not just in the context of Australia, but the world.

One of them, Peta Heinsen, lives in Noosa’s hinterland, surrounded by towering 50-metre-tall eucalyptus trees, the smell of star jasmine and a soundtrack of croaking frogs. Heinsen’s sister and business partner, Ilona Hamer, lives 15,000 kilometres away in Brooklyn, New York, with an office in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The soundtrack: skateboards. The surrounding towers: old brick tenements. It could not be further from Heinsen’s tropical surrounds and the Australian lifestyle that inspires Matteau’s refined, minimalist swimwear and clothing. But the partnership creates exactly the kind of nuanced approach to Australian-imbued fashion that has become so appealing to an overseas audience.

Matteau is part of a new generation of Australian fashion labels helping lead a global retail revolution – one that’s allowed emerging designers with no institutional support and no marketing budgets to swiftly taste international success. It used to take years, even decades, to achieve the kind of overseas penetration this new guard already enjoys. But Matteau and its cohort – Réalisation Par, Sir the Label, Matin and P.E Nation to name a few – have built global fanbases with a savvy, seemingly innate knack for Instagram and other digital channels. All share a global outlook, rigorously considered brand identities, a streamlined product offering and direct-to-consumer models that have allowed them to compete, and in some cases outplay, well-funded legacy fashion labels. These young designers aren’t just ahead of the game – they’re inventing a new one.

Australia is known around the world for many things – beautiful beaches, fine food and coffee, the Sydney Opera House – but our fashion designers haven’t always received the global recognition they deserve. This was due to multiple forces, among them, you used to have to go overseas if you wanted to raise your profile there. It also didn’t help that our fashion calendar clashed with the Northern Hemisphere’s, making attendance at Australian Fashion Week a difficult prospect for foreign buyers, stylists and press. Plus, our seasons are totally out of sync with the north’s.

Nonetheless, Collette Dinnigan, Martin Grant and Sass & Bide achieved international success in the ’90s and early 2000s with overseas runways, wholesalers and flagship boutiques. Later in the 2000s, the next generation made successful and lasting international thrusts: Zimmermann, Camilla and Marc, Bassike. And post 2010, designers such as Dion Lee, Kym Ellery, Lucy Folk and Patrick Johnson established international footholds after first making their names here. These recent success stories were rooted in the traditional way of doing business: opening stores or securing stockists locally, then taking on the world. Now, Australian labels can be global from day one. And the country’s relaxed lifestyle – woven into the foundations and fabric of our design – has become an international commodity.

Matteau launched in 2015 with just seven pieces of swimwear: three styles of brief, three bather tops and a one-piece. The label had an Instagram account months before you could actually buy anything on its website, and when it finally accepted orders, overseas demand was instant. Matteau is now stocked by a raft of influential online retailers including Net-a-Porter, Matches and Farfetch, plus countless boutiques in the Americas and Europe. International sales have grown season on season since launch. This time last year, 75 per cent of Matteau customers were Australian, and 25 per cent came from elsewhere. Now that figure is more like 50/50. “Our international sales will soon far surpass our domestic,” Heinsen says.

“The culture of the way people consume fashion and find out about it has completely changed,” says Hamer, a former Vogue Australia fashion editor, now freelance stylist. “Which has been a really great advantage for Australian designers because we’re so isolated.”

A direct-to-consumer business model leveraged through social media and custom e-commerce platforms has benefitted fashion labels all over the world. But for a country so physically remote – both from global fashion hubs and billions of potential consumers – the instant access to international dollars offered by these channels is a game changer. Because it has no borders, Instagram can catapult local designers into the social media feeds of gargantuan populations in Europe, America and Asia.

The first – and perhaps most famous – Australian symbol of this new ecosystem came in 2012, when Melburnians Erin Deering and Craig Ellis launched a neoprene swimwear brand called Triangl from Hong Kong. With no advertising budget, they relied on Instagram to promote their colourful bikinis. Three years later Deering was on the BRW Young Rich List: those bathers earned her a reported $36 million.

The lesson here: Australia’s isolation no longer delays or precludes global success. In fact, it can occur at breakneck speed. No need for bricks and mortar, and certainly no need for entire collections released twice or more each year.

That was the thinking behind Teale Talbot and Alexandra Spencer’s collection-less, season-less label Réalisation Par, which launched in 2015 with four dresses, one top and a skirt. The initial run of garments – mostly red and blue, emblazoned with stars and flowers – was instantly omnipresent on social media feeds and Australian streets.

Three years on, a cavalry of celebrity fans drive a hype machine so powerful that when Réalisation sells out of certain pieces, magazines such as Vogue and Elle run stories telling their readers when it will be back in stock, or where to purchase alternatives. Réalisation is one of the biggest, and fastest, Australian fashion success stories in recent history. It has no stores. It has no wholesalers. It steers clear of traditional collections and adds individual garments in an iterative process that ignores seasons and trends.

Overseas customers – largely from the US, UK and China – account for 80 per cent of its business, and more international shoppers visit its website than any other Australian label’s, according to digital research firm SEMrush.

“Social media has been an incredible tool for us – it’s the reach it provides,” says Talbot, now based in London. She’s not just talking about Réalisation’s own Instagram account, which is racing towards half a million followers. Three years ago Talbot sent a silk cocktail dress to British fashion personality Alexa Chung. Sales blew up after Chung wore the dress to a New Year’s Eve party in Miami and posted a snap to her millions of followers.

Similarly, when reality TV star and make-up mogul Kylie Jenner posted photos of herself wearing a pair of Dead Studios tights to her 50 million followers (that figure is now 117 million), the Sydney-based activewear label sold 30,000 pairs of tights in a week. US customers stormed the Dead Studios store, and US stockists followed. Today Americans account for 30 per cent of the label’s total sales.

These examples illustrate that marketing is no longer about getting your clothing on high-profile celebrities – it’s about getting them on the person with the largest social media following, though the two groups often overlap. Likes and follows translate to sales.

For Réalisation, Instagram has become so fundamental to its existence that it determines clothing releases. If enough users “like” pictures of a three-year-old blouse, Talbot and Spencer might decide it’s time to bring it back. “We can shoot something, edit and have it up on Instagram the next morning, and get a read on sales by that afternoon,” Talbot says. “It’s an incredibly fast way to look at demand, and how you can interact with your consumers, from the girl that’s in Adelaide, to the other one that’s in Paris, LA, or Sweden, or that small town in America somewhere.”

Nikki Campbell and Sophie Coote, founders of Sydney-based Sir the Label, launched an Instagram account as soon as their brand had a name. “We were 24 years old, doing it all ourselves,” Campbell says. “We just wanted to get our name out there. [Instagram] was inexpensive and took it international straight away.”

They uploaded photos of sample clothing before any garments went into production, and complemented that with other “random” images. “You couldn’t tell it was a clothing label at that time,” Campbell says. “People weren’t sure if they were getting a capsule collection or linen or what it was.”

This drove substantial hype so that when Sir eventually went on pre-order, it “pretty much sold out overnight in the majority of styles, all basically leveraged off Instagram.”

Sir was recently picked up by Barneys, the iconic New York department store. Most of the labels that launched as pure direct-to-consumer plays now also have thriving wholesale businesses. In this way, Réalisation and Triangl are the purest examples of the direct-to-consumer model – you can only buy their product from them. A recent pop-up at London department store Selfridges marks the first and only time Réalisation has crossed into bricks-and-mortar retail. If you want one of its romantic summer dresses or cult leopard-print skirts, the Réalisation website is your only option.

This doesn’t necessarily reduce overheads. Réalisation still has to pay for warehousing costs, and people to process and ship each order. Likewise, the benefit of reduced transport costs is dwindling as countries toughen up on taxes and duties, forcing companies to set up logistics chains in multiple locations in order to keep shipping worldwide. But this model has a huge effect on cash flow.

“In a wholesale model it can take anywhere from six to 12 months from the time a retailer places an order until the money is banked; not to mention the time and energy spent on trying to get these accounts paid,” Talbot says. “With direct-to-consumer you get paid before the order is even shipped. Managing cash flow, or lack thereof, is the biggest strain on small businesses, so eliminating this risk really solidifies the ability to manage growth.” (Selling direct to market also means designers make the full margin from cost to retail, rather than losing that mark-up to a wholesale partner.)

At a time when commercial rent in Australia is among the most expensive in the world, it makes sense for new designers to eschew physical stores, especially when they can communicate their brand and ethos so clearly online.

“Because we don’t have any bricks and mortar,” Talbot says, “our business is built on international consumers being able to see and desire the product in an environment, and it’s through social media that this happens.”

This notion of “environment” is important. Réalisation, Matteau, Sir the Label, P.E Nation – they sell clothing, yes. But fans buy into the lifestyle and personalities these brands promote as much as they do the products they’re selling. Ilona Hamer refers to the idea of a “universe”. If you follow Matteau on Instagram, for example, you’ll see photos of its white cotton sundresses and seamless lilac bikinis. You’ll also see images of abstract paintings by Paul Klee and vintage Architectural Digest spreads. Réalisation has an army of “dreamgirls” – beautiful women ranging from supermodels to more relatable friends and fans of the label – who wear its garments in the sun-drenched streets of LA, London and Paris. P.E Nation co-founder Pip Edwards uses her personal Instagram account (137,000 followers) to feed into the business’s (152,000 followers) – customers want to buy into her personal wardrobe and lifestyle.

This approach elevates fashion labels to something beyond a brand, generating cult appeal and making the worlds they depict covetable in themselves.

“It’s not just, ‘Here’s our product’,” Hamer says. “It’s: ‘This is the woman; this is our world; these are the things we’re interested in’.” As Heinsen puts it, their Instagram “has a point of view”.

Crucially, this view is rooted in a more sophisticated version of Australia than the expected sun, sand and surf. “What you see a lot of Australian swim brands doing is ‘sexy swim’ – that girl on the sand, laying in the wash,” Heinsen says. “We’re not that brand. We’ve never done a shoot like that on a beach and never will.”

Australia has developed a recognisable fashion vernacular that’s unpretentious, fresh and subtly evocative of our relaxed coastal lifestyle. Our designers use that DNA in specific and original ways. Some adhere to classic, clean and timeless styling. Others embrace femininity, nostalgia or technical sportswear. Whatever the product’s final form, international wholesalers – which have been vital in raising awareness and sales volume for our local labels – love that DNA, not least for its transeasonality, which means the clothing performs well year-round.

“The impression that Australia was only about swimwear and summer has definitely shifted,” says Elizabeth von der Goltz, Net-a-Porter’s global buying director. “We are seeing some great elevated basics and luxe daywear brands come out of the [Australian] market and perform extremely well.

“The collections were so diverse and unique, yet still spoke to an international audience, which is imperative to us as a global retailer.”

A crucial change in the timing of Australian Fashion Week has helped buyers like Net-a-Porter see these collections more often. In 2016 the event finally changed its schedule to run in May, not April, and pivoted to showing inter-season resortwear instead of mainline spring/summer collections. The change to a resort focus is important – it means overseas buyers have more budget to spend on new brands (by the time spring/summer rolls around, much of the season’s allowance has been allocated to historic accounts), and it gives budding labels (and risk-averse wholesalers) more time to sell through stock ahead of summer sales. “The new timing definitely makes it easier for international press and buyers to attend,” says Von der Goltz. In 2017 the number of attending buyers jumped by more than 50 per cent compared with 2016.

Net-a-Porter now stocks 36 Australian brands across fashion and beauty and soon it’ll add four more: Sydney’s Matin and Anna Quan, and Queensland’s Lack of Colour and Peony.

Labels such as Matteau, Matin and Sir first saw success with direct-to-consumer operations that bypassed the traditional halls of fashion retail. But that self-generated buzz quickly drew the attention of influential press and luxury retail players, which anointed them in the eyes of the fashion establishment. This recognition is significant for designers whose early success came from selling straight to consumers; it confers instant prestige and effectively acts as a siren call to other stockists.

“Securing Net-a-Porter [was] a milestone for Matin,” says Michelle Perrett, the co-founder of the Sydney-based refined-basics label. Seventy-seven per cent of its sales are to international customers, something that will grow with the Net-a-Porter acquisition. “They have a six-million-person audience and this partnership propels a brand into a whole new global space,” Perrett says.

That’s underselling it. Six million women read, browse and shop Net-a-Porter each month, but its global reach – with social media and other platforms – is more like 28 million, meaning a new stratosphere of international brand awareness for a label with just 20,000 of its own Instagram followers.

Why is this international penetration so important? Sustainability. Once they’ve reached a certain point, our local labels need bigger populations before they can scale their businesses. Retail in this country has been a tough business since the global financial crisis. International high-street brands arrived in droves, commercial rents and wages increased, and the same platforms (Instagram, Net-a-Porter and so on) now boosting some local labels also took consumer dollars away from others.

In the past five years stalwarts Josh Goot, Lisa Ho, Kirrily Johnston, Life With Bird and Willow all closed, and Lover and Oroton were forced into voluntary administration. (Goot has since co-founded an innovative direct-to-consumer pure-play with New York-based Wardrobe NYC, selling luxury clothing staples as a set rather than individually.)

“The Australian market is so small in terms of wholesale,” says Dion Lee, one of the past decade’s most celebrated Australian designers. “It’s fairly impossible to only rely on the Australian market to continue to grow a brand. I would say it’s unsustainable.”

This mentality is baked into the next generation. Three-year-old athleisure label P.E Nation, for example, already has 200 international stockists thanks to founders Pip Edwards and Claire Tregoning’s backgrounds at Ksubi, General Pants and Sass & Bide. The label’s sales and PR agencies have been based in Los Angeles and New York since day one. “We were trained to think global,” Edwards says. “It wasn’t an option to just be Australian.”

This new, more profound era of overseas success didn’t come about by accident. Alongside clever designers and technological shifts, there have been monumental strategic efforts – years in the making – on the part of local industry bodies to raise Australia’s global fashion profile. This has fostered a receptive and important overseas industry audience – in the media, and in showrooms – eager to pounce on impressive direct-to-consumer labels like Matteau or Sir.

The Australian Fashion Council (AFC) – originally founded as the Australian Fashion Chamber – has been one of the local organisations instrumental to redefining and elevating Australia’s overseas fashion credentials. It was set up in 2015, largely at the behest of Vogue Australia editor-in-chief Edwina McCann, to clarify and promote the Australian fashion narrative globally, and help designers be better business people.

Together with The Woolmark Company – a subsidiary of Australian Wool Innovation – the AFC has fast-tracked the international expansion of numerous local labels.

For Woolmark, the development of a strong, marketable brand of Australian fashion has been central to a strategy initiated back in 2010. Woolmark’s mandate is to promote and drive demand for Australian wool on behalf of some 60,000 sheep breeders, and Woolmark CEO Stuart McCullough believes one of the best ways to do that is by deepening relationships with the pillars of the global luxury fashion industry.

As part of that strategy, in 2012 it relaunched its International Woolmark Prize, which had run for a few years in the 1950s – two of its early winners were Yves Saint Laurent and Karl Lagerfeld – to highlight first-class emerging fashion talent around the world.

Menswear- and womenswear-prize finalists are flown to cities such as Florence and New York, where their collections are paraded in front of judges from the top echelon of the global fashion industry, including influential designers (Donatella Versace, Diane Von Furstenberg, Victoria Beckham, to name a few), media, stylists and buyers. Next year Australia’s Albus Lumen will compete in the final stage in London, and we’ve sent a number of labels to the finals since 2012 including Dion Lee, Christopher Esber, Strateas Carlucci, Bianca Spender and tailor Patrick Johnson.

In 2015, Johnson travelled to Florence for the menswear final after his eponymous suiting label won the Australian regional competition, which “laid the foundations” for him to grow his business internationally.

“We now have showrooms in New York and London, along with a partnership with Barneys in the United States,” Johnson says. That affiliation spans five Barneys stores, with a dedicated space inside the Madison Avenue flagship. On top of that, Johnson’s is the first and only Australian menswear label to be sold on Mr. Porter, the pinnacle of men’s online luxury retail; it joins the likes of Prada, Gucci and Tom Ford.

Beyond the prize, Woolmark works closely with the AFC to ensure Australian designers are present at major international fashion events, from fashion weeks to prestigious trade shows such as Pitti Uomo in Milan.

The AFC’s Designers Abroad program has enshrined this overseas presence, taking a group of local labels to showrooms during New York or London or Paris fashion weeks every year since 2015. Australian designers are introduced to buyers, journalists and other influential figures they otherwise might not meet for years, if ever. Labels are generally watched for multiple seasons before a buyer commits to them, so the AFC escorts labels to sequential fashion weeks.

“When we started doing it one of the criticisms we always got about Australians is that they were inconsistent,” says Courtney Miller, the AFC’s former general manager. “That’s why [Kym] Ellery has moved to Paris or Dion [Lee] has moved to New York – to accelerate that process and to build that deeper connection in order to make their brand more successful.”

Matteau’s Hamer, Réalisation’s Talbot and Spencer – they also live overseas. Sir shoots its campaign imagery in paradise-like locations on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico, or the French Riviera, not Bondi Beach. Many of these new labels talk about a European sensibility or a subtler interpretation of their Australian moorings and what defines their Australianity is less about physical location and more about an idea and a lifestyle: big open skies, salty air, coastal cities, sunny weather and a relaxed attitude.

Australians have always looked outward as well as inward for inspiration (it’s one of the reasons our creative industries, from fashion to design to hospitality, are so rich) and a more nuanced interpretation of what it means to be Australian has been crucial to attracting the global fashion industry’s attention.

The connective tissue of these brands is easy, transeasonal style and luxurious natural fibres – garments that speak to a culture of sun, travel and outdoor living.

“Our culture is coveted,” says Woolmark’s McCullough. “That surf, rural lifestyle that we live … is really starting to be noticed. Consumers want a story with their product, so that a brand came from that part [of the world means] they’ve got a good story to tell. That’s something we’re doing very well.”

We chose to work with Montana Cox and Sam Bisso because, like the labels in this story, they are Australian talents with global outlooks, at the top of their fields. Cox splits her time between New York, London, Sydney and her hometown of Melbourne. After this shoot, Bisso flew to Hong Kong for another assignment, followed by a trip to Paris to shoot for German Elle.

Model: Montana Cox

Photographer: Sam Bisso

Assistant: Will Linstead

Stylist: Kate Gaskin

HMU artist: Julie Provis

Studio and equipment: Rokeby Studios

Creative team and production: Hart & Co

Thanks to: Crumpler for supplying luggage