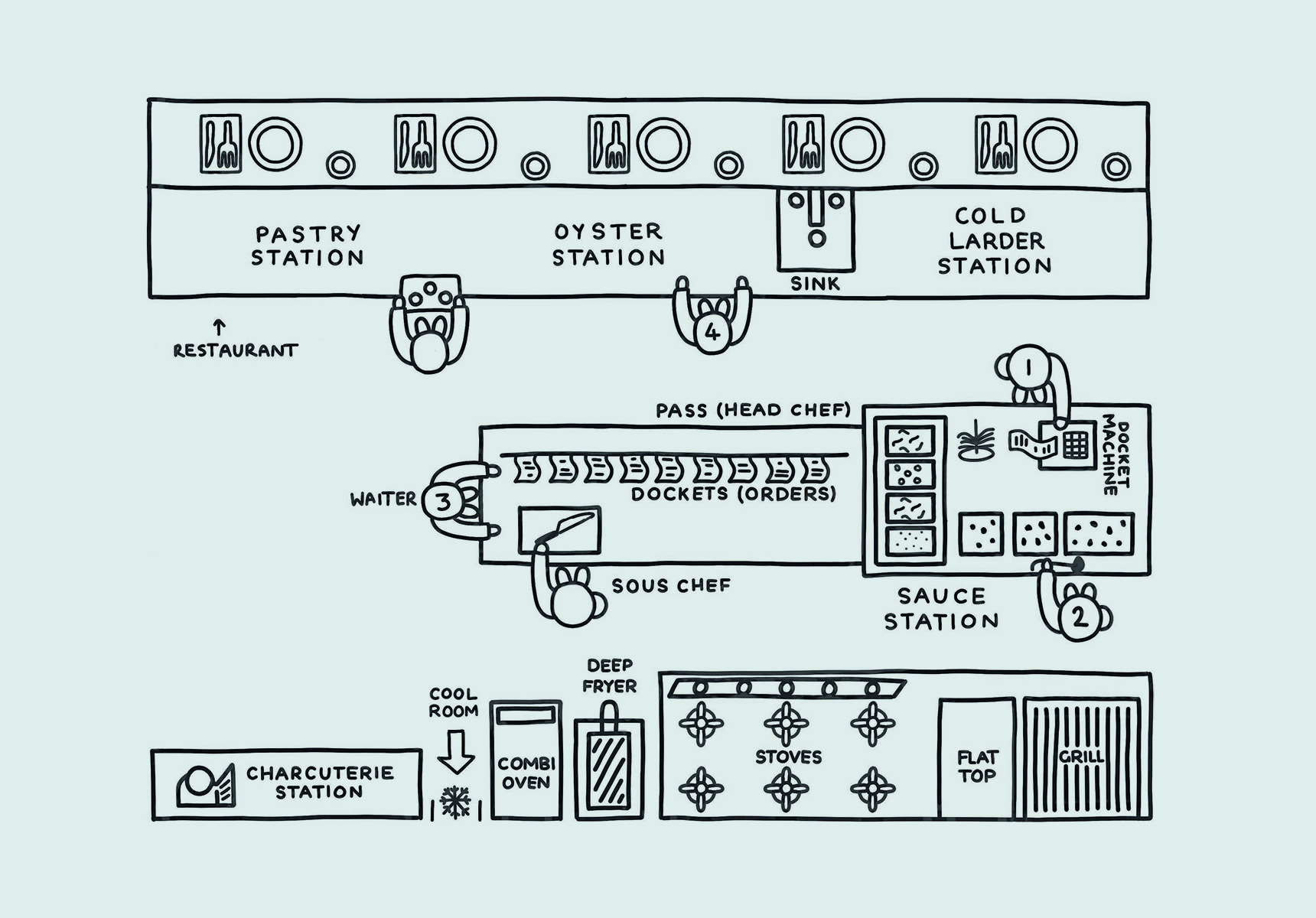

Cumulus Inc, Melbourne

Sam Cheetham is the captain of this small but prodigious open kitchen in the CBD, which runs all day and serves European share plates. The head chef says his job is a bit “like sudoku” – 20 dockets at any one time, five chefs to manage, and an endless torrent of dishes arriving at the pass. Needless to say, cooking is far from his only skill. When we arrive, table 101 has just placed its lunch order with its server, Evelyn. – TB

1. The docket is received at the pass. Orders spit out rapidly, so Cheetham is never too far from the printer.

2. In a loud voice, Cheetham assigns each section of the docket to a different station. “Three Clares!” gets the oysters underway. “One Scotch fillet on the back!” tells the sauce chef to begin cooking the beef at the hot section (a 30-minute task). Each chef acknowledges the order with a loud “Yes chef!”, so Cheetham can mark the item off with a highlighter.

3. The shucked oysters arrive for inspection by sight. They pass muster. Cheetham summons a waiter by dinging his bell and says “three Clare de Lunes for table 101”. The waiter repeats the order back to him, then it’s off to the table. Cheetham tastes every other type of dish before it goes out.

4. Cheetham assigns the snacks and starters. He first calls the spanner crab with fried green tomato to the hot section. Once cooked, he assembles the dish himself at the pass, requesting “one tuna tartare” from the cold larder section at the same time. The tuna arrives by the time Cheetham’s done plating the crab. Both dishes are sent off.

5. A pause, and a quick consultation with Evelyn to see if 101 is ready for mains or not.

6. Mains. Cheetham first calls out “one snapper” to the hot section, knowing it will take five minutes to cook and garnish. The beef, which has been resting, is called for its final preparation with shiitakes and finishing sauces. Cheetham tags the potatoes onto the order and calls the cosberg salad to the cold larder. Finally, he yells out “two minutes!” – a cue for everything to be plated and sent to the pass for inspection and service.

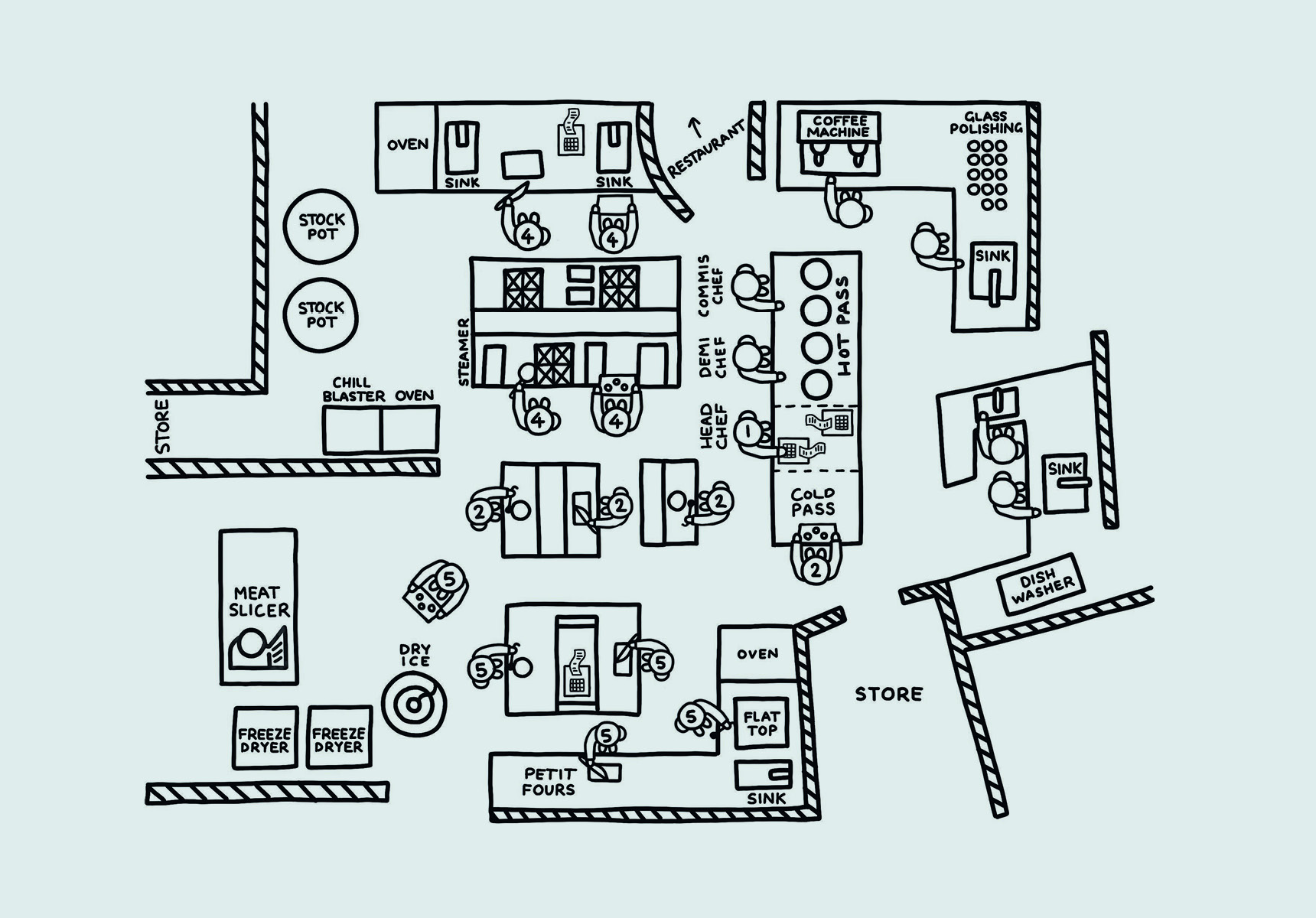

Quay, Sydney

With some of Australia’s finest food served alongside one of the world’s greatest views, chef Peter Gilmore’s flagship restaurant is not only a singular dining experience, but a true celebration of Australia. The outlook may be dazzling, but the ballet performed behind the scenes is equally impressive. Ten kitchen stations – one for each course in Quay’s astonishing degustation – buzz with activity. Each table’s culinary journey is mirrored by a docket’s winding path around the kitchen. – TL

1. When a new table arrives, the primary docket printer (next to the head chef) indicates whether the diners have chosen six or 10 courses and if they have special dietary requirements. He yells out the order to the rest of the cavernous kitchen (“four 10-course, one pregnant, one vegan!”), which begins preparing a series of amuse-bouches immediately. Tim Mifsud and Troy Crisante currently share the role of head chef at Quay. Later, three extra printers around the kitchen notify the relevant chefs that a table has been cleared and is ready for its next course.

2. The first three dishes in Quay’s epic 10-course feast are made at three cold-dish stations; one station per dish. Although nothing is actually cooked here, there’s plenty of activity, such as assembling the intricate Hand-Harvested Seafood course. This involves trimming octopus to order, then precisely arranging it in a stone bowl so all the tentacles curl the same way, on top of pippies and slices of raw scallops.

3. The head chef inspects the three cold dishes at the pass and dispatches them.

4. Four hot stations spring into action one-by-one as they receive dockets to say the table is ready for its next course. Dishes such as glazed roast duck, smoked pork jowl in jamon-infused butter and delicate crab custard are sent to the pass. Floor staff waits to whisk the plates away as soon as they’re ready.

5. The dessert courses are put together in the corner, wrapping up both the meal and the docket’s trip around the kitchen. A dry-ice dispenser intermittently sends puffs of fog floating around the chefs’ feet as they craft the restaurant’s elaborate White Coral dish. This is also the section behind the savoury crumpet-and-caviar course, the crystallised caramel dessert and the petit fours that round out the several-hour meal.

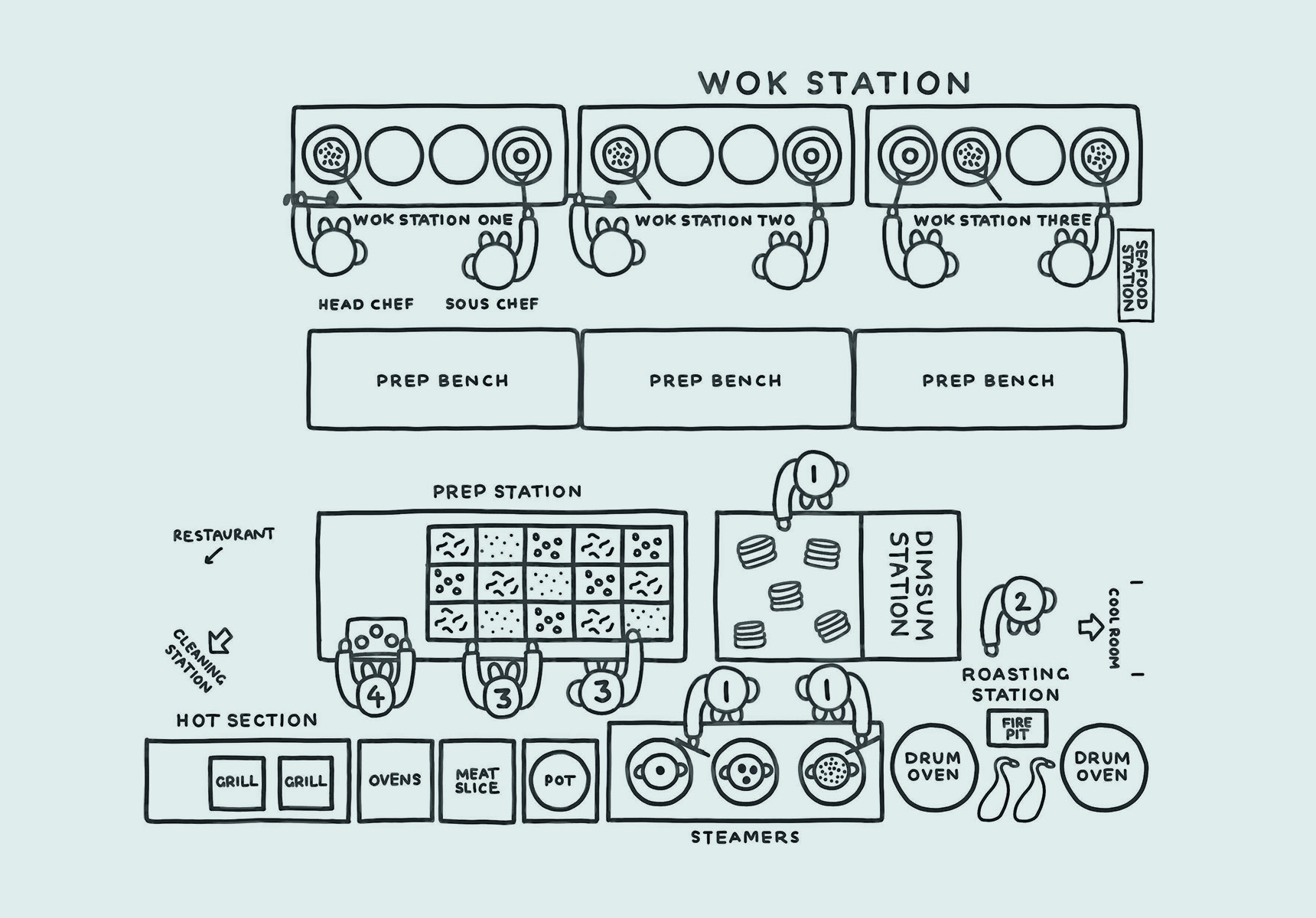

Flower Drum, Melbourne

This Cantonese fine-dining institution doesn’t really have a head chef. Compared with Western kitchens – where a head chef is like the conductor of an orchestra – Flower Drum has a fairly horizontal hierarchy. On a typical service, you’ll find co-owner and executive chef Anthony Lui at one of the four wok stations, preparing the more delicate, expensive items such as abalone and crayfish. Otherwise, there are six independently operating stations, each with their own pass. Waiters – not chefs – control what to start cooking and when. Each station deals with about 20 orders at a time, and often relies on other parts of the kitchen to help with certain elements. Timing and communication are key. – TB

1. Dumplings – Flower Drum serves everything from Black Angus beef siu mai to mud crab sui long bao, all parcelled up throughout the day so they’re ready to cook on demand. Dumplings are cooked inside bamboo steamers placed in one of three mammoth cylinder steaming pots.

2. Peking duck (four minutes later) – A waiter instructs the roasting chef to prepare the duck. Ducks are cooked over two days of marinating, stuffing, drying, hanging and eventually roasting in a giant drum oven for 35 minutes prior to service. The roasting chef chops up the duck to finish it. There’s also communication with the dim sum chefs, who need two minutes to prepare the pancakes in the steamer.

3. San choi bao (nine minutes later) – On the waiter’s command, a preparation chef assembles ingredients such as quail meat, Chinese sausage, onion, shiitake mushrooms and water chestnuts to make this quintessential hot-cold Cantonese dish with a warm mince filling served in cool cups of iceberg lettuce. Prep chefs operate the grills and oven, but san choi bao ingredients go to a wok station for stir-frying. Waitstaff act as middlemen between the two stations, passing bowls of raw ingredients to the wok chef and receiving back the cooked product.

4. Assembly and service – Waitstaff assemble and garnish the dumplings, duck and san choi bao at each station before passing the dishes off to food runners. The waiter in charge of the table meets the food at the table to serve it.

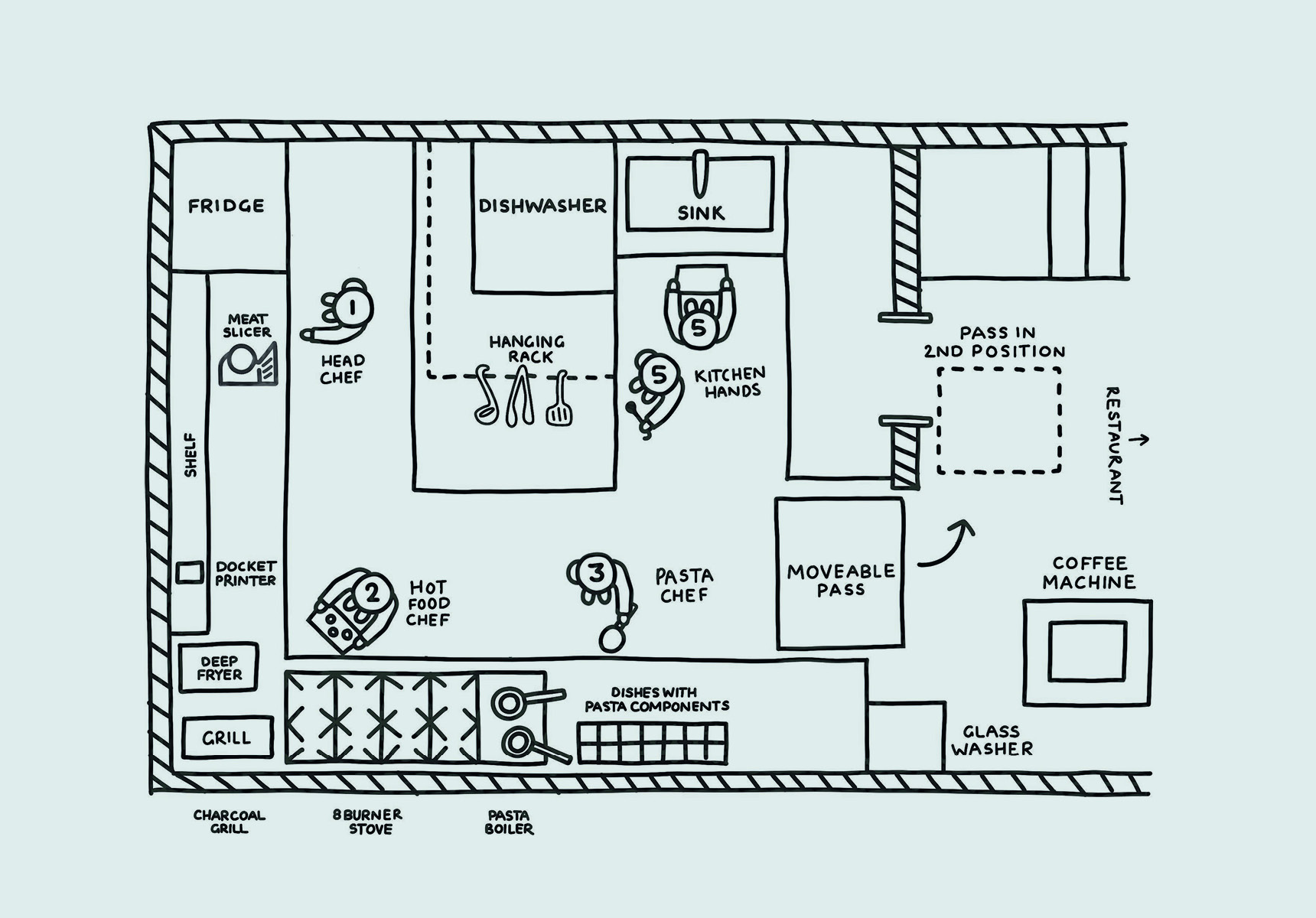

10 William St, Sydney

Like Cumulus Inc, this esteemed wine bar serves broadly European share plates, but from a famously tiny kitchen. Equally renowned is the kitchen’s impressive list of alumni, including Dan Pepperell (Alberto’s Lounge), Luke Burgess (Garagistes), Mike Eggert (Totti’s) and Jemma Whiteman (Lankan Filling Station). Trisha Greentree took the helm in March, bringing the produce-forward style she picked up during her time as senior chef de partie at Victorian restaurant Brae. – TL

1. From the snug “cold food” corner, Greentree checks the incoming dockets, which group dishes according to the order each table wants to receive them in. Wordlessly, she passes a copy to the pasta chef, and gets to work plating shared starters that don’t require a hit of heat. Tonight it’s French breakfast radishes with ricotta and caviar, and a clever persimmon, pear and lardo carpaccio. Later in the meal she also looks after salads and cheeses.

2. After Greentree has secured the docket in their shared docket rail, the hot food chef gets immediately to work preparing warm starters such as lemon and thyme focaccia and pig’s head croquettes. Subsequent print-outs later in the meal alert him to start grilling, baking, frying, steaming or poaching larger shared dishes such as hanger steak with parmesan and mustard greens.

3. The pasta chef springs into action when Greentree hands him subsequent dockets saying the table’s been cleared, re-set and is ready for house-made pappardelle, linguine, orecchiette or another splendid combination of eggs, flour and water. The same chef looks after dessert at the end of the meal, scooping prepared tiramisu into bowls and sprinkling with cocoa.

4. Greentree farewells the finished dishes at the pass, casting occasional glances over the plates when time allows. The pass is a trolley that blocks the only doorway to the kitchen and rolls away if a chef needs to escape.

5. Empty dishes are returned to the kitchen to be washed and dried by kitchenhands. During service these all-purpose assistants can also be seen passing equipment to chefs, peeling potatoes and picking herbs.

Glossary

The pass – a large counter, typically lit by heat lamps, where orders are printed and assigned, and where a head chef inspects (and often tastes) each dish before it’s collected by a waiter. The nerve centre of a kitchen.

Brigade de cuisine – a military-like kitchen hierarchy developed by French chef Georges Auguste Escoffier in the early 1900s, which most modern kitchens use a simplified version of.

Executive chef – a highly experienced chef who manages the creative and operational aspects of one or more kitchens: designing menus, hiring new staff, ordering raw ingredients and so on.

Head chef – the second in command, who runs the kitchen during service and may have a hand in creative aspects of the menu. They spend most of their time at the pass, receiving dockets and checking plated dishes.

Sous chef – next in command after the head chef; often runs the kitchen on quieter days. Typically coordinates the kitchen’s stations and various chefs de partie. Larger kitchens often have several sous chefs.

Chefs de partie – trusted line chefs who run a kitchen’s varied stations, such as the grill station, fry station and cold station. May or may not be assisted by demi chefs to cook meat, assemble salads and so on.

Commis chefs – junior chefs who do the most menial work at each station, such as shelling peas or de-scaling fish. They also look after each station’s utensils. Typically training to become a demi or chef de partie.

Kitchen hands – in charge of pot-washing and other miscellaneous tasks. In some restaurants, they may also do prep work with commis chefs. Good kitchen hands anticipate what equipment the kitchen needs next and prevent delays.

This story originally appeared in Melbourne print issue 26 and Sydney print issue 18.