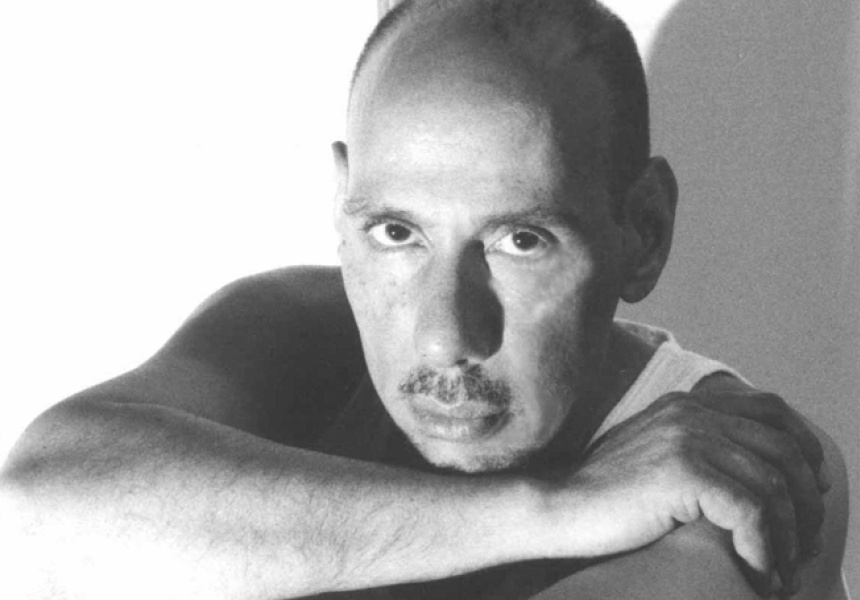

Nicky Siano was 16 when he left his childhood home in Brooklyn and moved to Manhattan's gay haven, Greenwich Village. It was 1971. Within a year, before he was even legal, he had opened the Gallery – a nightclub that would dominate the city's social circuit, and eventually, go on to inspire the legendary Studio 54. But Siano's story isn't really about a nightclub. As he explains in a new documentary, Love is the Message, there were far more important things afoot.

Just two years earlier, it had been illegal for two New Yorkers of the same sex to dance together, Siano says. Gay men and women were confined to the city's worst haunts: seedy dive bars run by the mafia. Though such venues bribed the police like clockwork, they remained easy targets for raids. Every few weeks, Siano says, “a few queens” would be dragged out of a club, hauled downtown and “processed”. Until one famous weekend in June 1969. At a bar named Stonewall the crowd fought back the invading cops, sparking a week-long series of riots and eventually, emancipating fellow queer people across the country.

Siano started hanging out in The Village soon after and discovered, “A life where gay people weren't hassled for who they were.” As a teenager, he had frequently been beaten and abused because of his sexuality. “I starting hearing about these places where people went to dance,” he says. “It sounded really interesting, but I was too young. Then I found this place called The Firehouse.” At the Firehouse, profits were donated to Lambda Legal, a fund formed post-Stonewall to defend gay people jailed during the course of liberation activities. The club didn't have an age limit.

We think you might like Access. For $12 a month, join our membership program to stay in the know.

SIGN UPSiano had been interested in folk and rock before, but club music blew his mind. “I'd never heard R’n’B records and things you could dance to,” he says. “I remember this one song called Rain by Dorothy Morrison. I had to own that record; I went to more than 30 record stores looking for it.” Songs such as this embody the spirit of the era, he believes. “The Vietnam War had basically been stopped by public pressure. People were feeling very celebratory and powerful. You could hear it in the music.”

By this time, Siano was 16, a year ahead at high school and six months away from graduating. But then something big happened. As he was walking to school, two guys jumped him and beat him up. “I went home and I was crying going, 'Fuck this, I can't stay here!’” he recalls. “I remember having a suitcase, packing it and renting a hotel room in The Village. It was like $10 a night, and I'd saved up about $500 from my paper route, and I just started living there.”

Siano's girlfriend – he was bisexual at the time – came with him. They rented an apartment and went partying on weekends. Problem was, they were still too young for most clubs. Then they found The Loft, or what Siano calls, “The place where the whole scene started.” Held at the house of one David Mancuso, The Loft is often credited as disco's ground zero. It was here that the idea of using a first-rate sound system was born, and the ideals of togetherness and inclusiveness nurtured. Mancuso was white, but his guests were mostly black, gay and Hispanic.

“David started expanding on what sound should be, and really honing in on making an environment that was way beyond a little bar with two speakers,” Siano says. “That's when I decided: I have to play records.” After writing a business plan, he went to his brother, who'd just settled an accident pay out. The pair opened The Gallery with $15,000.

What The Loft had done for a small group of friends, the new club did for 800 people every weekend, while retaining the experimental edge. “I was the first person to develop bass horns, and I had three turntables,” Siano says. “The sound system was the main, main thing.” When The Loft closed, the 17-year-old's venue became number one in town. “It was like a fashion industry watering hole,” says Siano. “We dealt with the same people every week, so it became very communal and friendships started to develop.”

This was in sharp contrast to the exclusive attitude at Studio 54, which opened in 1977, the year The Gallery closed. Steve Rubell, co-owner at the new club, had been a long-time member at The Gallery and took Siano and several other staff with him. But where journalists and movies like 1998's 54 have glorified the club's role, many original scenesters see it as the point where disco took a wrong turn, losing its original ideals to an apathetic white audience.

“At the Gallery, we were playing R’n’B records,” Siano says. “Very much in the Philly vein – Norman Harris, Gamble and Huff. They were very melodic songs, always with a message. If it was about love, it was a serious story, you know, 'I fell in love and I lost her.' Or, it was a story about, 'Spread the love epidemic all around the world, we should help people, we should band together. We can do it, we're brothers and sisters and that kind of thing.”

Towards the end of the ’70s, he says these themes were overtaken by superficiality: “Let's party, let's party, let's dance dance dance! What do you wear? Fiorucci, Gucci, Fiorucci, Gucci!” What had once been, “Within and beautiful and spiritual” became blingy and external; something to be bought and owned. “To me, the two are like God and The Devil,” Siano says.

These days, what many of us think of as disco – Abba, The Bee Gees, etc. – is really the work of bandwagon-hopping record companies, and bears little connection to the music which soundtracked Stonewall, The Loft and other crucibles of gay pride. Here are five classics Siano believes represent real disco:

MFSB – Love is the Message

Eddie Kendricks – Girl You Need a Change of Mind

The Trammps – Love Epidemic

War – City Country City

The Isley Brothers – Get Into Something

Nicky Siano will play at The Spice Cellar for Vivid Sydney on Thursday June 5.

vividsydney.com/events/vivid-music-spice-meets-studio-54-w-nicky-siano-nyc