“The Harbour City”. It’s a perfectly adequate nickname for our fair city, which is indeed located on a beautiful harbour. But it’s not romantic like “The City of Love”, sexy like “Sin City” or even catchy like “The Big Apple”. We have a better idea: “Rum City”. It’s snappy. It implies swashbuckling good times. And our history 100 per cent supports it.

Parliament House, one of Sydney’s oldest buildings, was originally part of the General Hospital. In 1816 – the year it was finished – locals called it the “Rum Hospital”. As the story goes, England was reluctant pay for a big, costly building in what it saw as an inconsequential penal colony. So Governor Lachlan Macquarie turned to a trio of local businessmen and offered them free convict labour and a monopoly on rum importation – up to a total of about 200,000 litres – to get the job done. That’s right, our stately old Parliament was literally paid for in rum.

This was fairly normal at the time. Coins were scarce in British colonies and rum was often used as currency. From about 1792 the New South Wales Corps, a sort of proto-police force, began using its power to control the import trade, earning itself the nickname the “Rum Corps”.

We think you might like Access. For $12 a month, join our membership program to stay in the know.

SIGN UPTwo governors tried – unsuccessfully – to end this profitable monopoly before the appointment of the notoriously tough William Bligh. He was given strict orders from England: halt the use of rum as currency. Within a few years he’d pissed off several powerful people in the colony, including the head of the Corps, Major George Johnston, and his associate, John Macarthur.

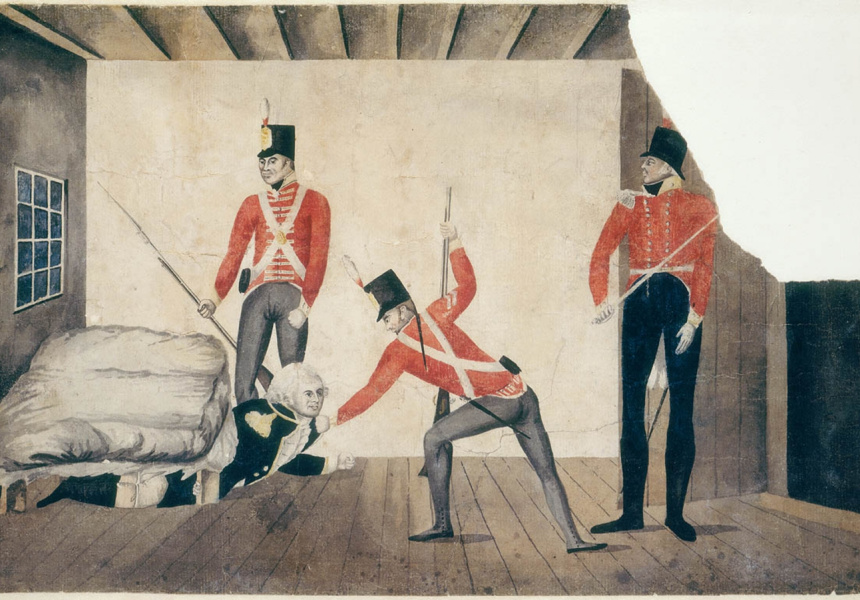

Such was the setting for 1808’s Rum Rebellion, a military coup that saw the Corps march on Government House and arrest Bligh, leaving control of the colony up in the air. It was two years before order was restored – a speedy-ish resolution given it took a whole year to sail to England, deliver news, receive instructions and return home.

The Rum Corps was recalled to England and replaced by the 73rd Regiment of Foot, led by Macquarie. He became governor of NSW in 1810 and quickly brought the rum trade under control, though even he had to leverage it to pay for expensive public buildings such as the General Hospital.

They say you should never let the truth get in the way of a good story, but we’d be remiss not to mention a couple of things at this point.

Firstly, in the 18th and 19th centuries “rum” was a generic term for hard spirits, and was just as likely to refer to something distilled from wheat or other grains as from sugar cane, like real rum.

Secondly, Michael Duffy, author of Man of Honour: John Macarthur: Duellist, Rebel, Founding Father, says with convincing authority that the Rum Rebellion wasn’t about the rum trade. Not only, anyway. It was more a long-running power struggle between businessmen who wanted to convert Sydney into a functioning, free market economy, and governors who wanted to continue running it as a giant prison. And the term “Rum Rebellion” was apparently coined 47 years after the fact by William Howitt, a teetotalling puritan out to demonise alcohol.

We still reckon Rum City is a great nickname for Sydney. Especially since rum – real rum – is making a comeback. Though we’ve taken a while to get there, that comeback is the entire reason for this history lesson of an article.

In March Rosebery’s Archie Rose Distilling Co – previously a vodka and gin specialist – launched Virgin Cane Rhum. This one was distilled in 2016 using cane sugar grown in Condong, northern NSW, then matured in ex-bourbon American-oak barrels for just over two years. (The spelling “rhum” denotes the use of fresh cane juice, rather than molasses.) The tasting notes mention chervil, olives, fresh earth and, oddly enough, marshmallow. There are just 182 bottles available and they’re a princely $199 each, but this is the beginning of a more concerted rum program from Archie Rose. We can’t wait to see more.

A bit further north, in Surry Hills, the 10-month-old Brix Distillers is on a single-minded mission to improve rum’s reputation and “[educate] a new, more discerning audience to appreciate the qualities and subtleties of one of the world’s great spirits”. Archie Rose’s former head distiller, Shane Casey, is at the controls and recently unveiled Brix Gold ($87), which drinks writer Mike Bennie calls “gloriously soft, honeyed, caramel-y and lightly spicy”. This rum wasn’t actually made in Sydney – it’s a blend of five- and eight-year-old rums from Barbados, also aged in former bourbon casks.

Brix Spiced (also $87) is a blend of local and Caribbean rums infused with cinnamon, vanilla, grapefruit, mango, macadamias, native lemongrass and bush currants.

And if you’re really keen for that genuine 1808 rebellion flavour, there’s Brix White ($75), an un-aged rum made in Surry Hills from Aussie sugarcane.

Let’s do it. Rum City. Rum City. Rum City.

This story originally appeared in print issue 18.