When John Kaldor was 12 years old his mother made a controversial decision: she agreed to let him stop school. She had one proviso: he gain an education in the classics by visiting all the galleries and museums their new city, Paris, had to offer.

The Wizard of Oz

John Kaldor helped rewrite Australia’s status as a cultural backwater, bringing the world’s most audacious artworks and their creators to the country, beginning in 1969. But his name is little known outside art circles. An ambitious retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales should change that.

Mrs Kaldor’s decision was a sage one. Her young son had already lived through the horrors of World War II only to flee the family home in Hungary with his family and end up stateless, en route to who knew where. Fitting into a new school in a new country wasn’t going to make his life easier.

She must have known her decision would profoundly affect Kaldor’s life, but she couldn’t have guessed the impact it would also have on the other side of the world, in Australia.

John Kaldor isn’t a household name, but it should be. Over the past 50 years his deft hand has helped shape the Australian contemporary art scene; he’s brought to the country the world’s most influential artists – often long before they themselves were household names – and changed the way we think about art in the process.

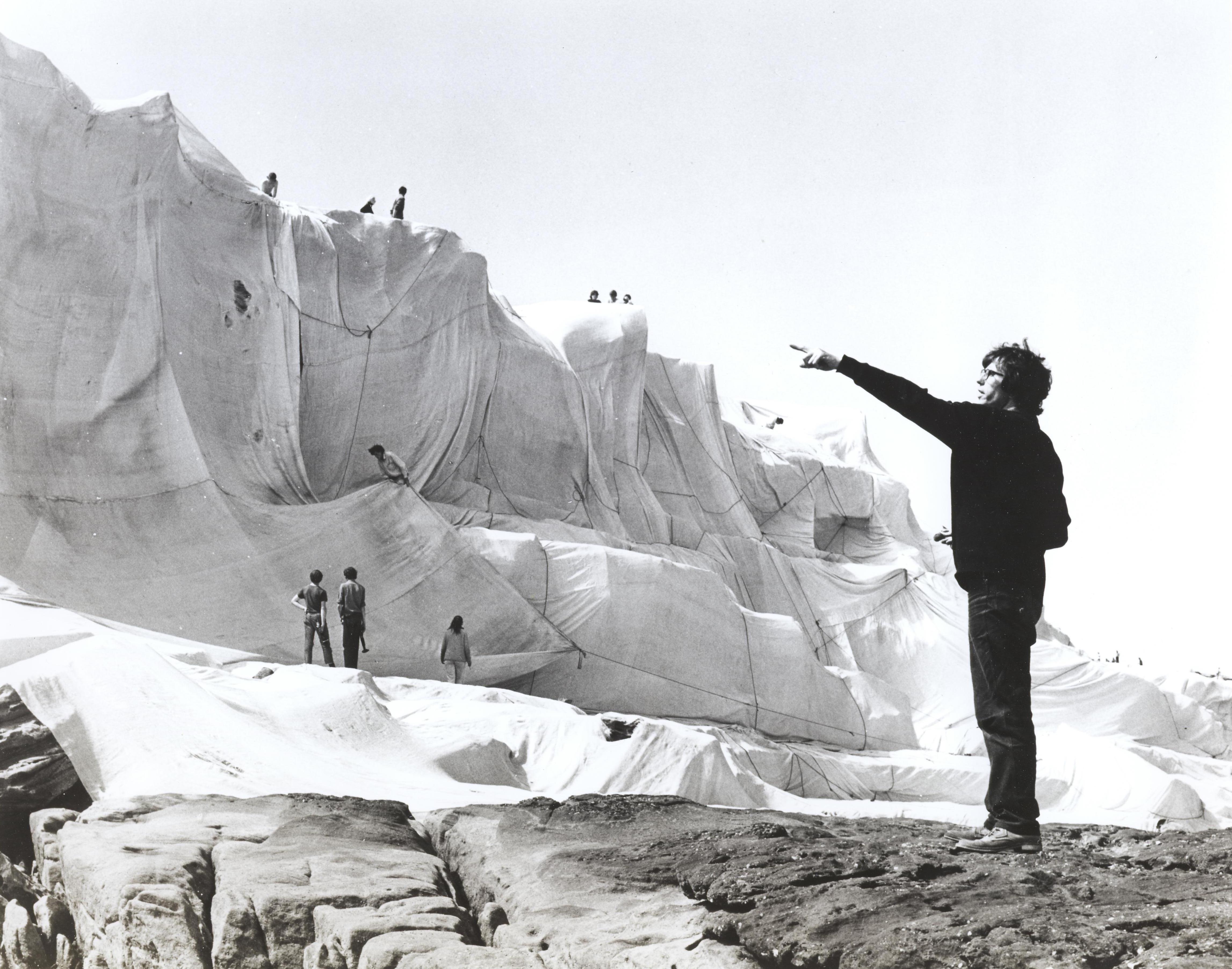

No project is more representative of this than Kaldor’s first: he brought Bulgarian-born environmental artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude to Australia in 1969 to wrap 2.5 kilometres of Little Bay’s coastline in fabric. Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet, Little Bay was named the most important art event of the year by Time magazine and at the time was the largest artwork ever created. It thrust Sydney and Australia into the global conversation at a time when we were largely still perceived as an irrelevant cultural backwater.

And while Christo and Jeanne-Claude would later become renowned for these gargantuan works of “land art”, including wrapping the Reichstag in Berlin and the Pont Neuf in Paris, Little Bay was their bold debut. It dominated local and international headlines for weeks.

In the ensuing decades, with 34 such ambitious projects realised by his Kaldor Public Arts Projects, the headlines have continued. Apart from Wrapped Coast, every artwork shown by Kaldor Public Art Project (KPAP) has been free to the public.

As KPAP celebrates its 50th birthday this year with a sprawling retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Kaldor’s legacy looms larger than ever. But while he’s lent his name to KPAP, he prefers to let the art speak for itself. He remains steadfastly private – some say shy – and has largely chosen to live his 70 years in Sydney out of the limelight.

KPAP is based in Lilyfield in the city’s inner-west. The team includes nine full- and part-time staff, which increases to around 15 in the lead up to a project.

In person Kaldor – bespectacled, with a distinctive grey and white beard – is somewhat inscrutable. Always stylishly dressed, he still exudes a European sensibility despite having left the continent so many years ago. The softly spoken octogenarian is curious, intelligent, a good listener and enjoyable company.

“From the beginning I wanted to bring to Australia the leading artistic movements internationally, whether they’re sculpture, performance or dance,” Kaldor says. “I have to admire the artist, I have to feel we could work with the artist and that the proposed project is doable, even if it’s difficult; and that the work will mean something for our audience, help in the understanding of what’s happening with contemporary art.”

In 1973, for example, Kaldor introduced Australians to British performance artists Gilbert & George, and their daily, five-hour-long “singing sculptures”. Edmund Capon, the former AGNSW director, would later call the project “a defining moment in the history of art in Australia”.

And there were others.

In 1976 he backed a series of events featuring Korean American artist Nam June Paik and cellist Charlotte Moorman. Moorman performed naked with a cello Paik carved from ice, suspended high above the Sydney Opera House forecourt from a bunch of enormous coloured balloons. A related performance saw her and another cello smothered in 13 kilograms of chocolate fudge.

In 1996, thanks to KPAP, Sydney hosted pop-culture sculptor Jeff Koons’s joyful giant Puppy, made with 60,000 cascading plants. Kaldor also brought out the American father of conceptual art, Sol LeWitt, and the world’s most famous performance artist, Marina Abramović. The abiding theme involves works that are sometimes challenging, often quirky and always surprising.

“John helped create an audience for contemporary art in Australia,” says Nicholas Chambers, the curator of modern and contemporary international art at the AGNSW. “What’s remarkable is that he did so not by following the safe path of exhibiting artworks already validated elsewhere, but by collaborating with artists to realise new, leading-edge projects here. The intended audience has never been art-world insiders … but a broad public who left with new ideas about the possibilities for art – that it could be wildly ambitious and exist quite independently of museums and galleries.”

As much as possible, Kaldor seeks to take art outside the traditional white cube and into interesting or historic sites. This challenges the artist, anchors the work in Australia and, most importantly, often captures an unsuspecting member of the public off guard. He cites Anri Sala’s 2017 project The Last Resort – in which the Observatory Hill Rotunda became an impromptu drum performance site responding to a contemporary interpretation of a Mozart concerto – as an ideal project.

“My preference is unusual spaces because then you get an audience whose destination wasn’t to go and see art, they just discover it. I’m quite evangelical about art and to preach to the converted is easy but to convert the heathen is much more satisfying,” he says, with a twinkle in his eye.

“In the case of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, I don't think anyone in this country had seen or experienced anything quite like that,” says Dr Deborah Hart, the head of Australian art at the National Gallery of Australia. “It’s not just that it was something public – it was something thought-provoking. It wasn’t just about taking art into the public sphere but the way he encouraged people to think about and experience that art. The relationship to the art was different to what we'd seen before … Even when he worked in a gallery context, it was about making these places feel alive.

“His impact has been truly groundbreaking … To have someone of John’s vision – to realise what we needed here – helped to inspire a lot of artists and the public in general to think about art differently.”

Kaldor, his younger brother Andrew and their textile-designer parents, Andrew and Vera, survived World War II in Hungary before fleeing once the country came under communist rule. In 1948 the family escaped to Vienna with little more than the clothes they wore, before travelling to Paris.

With scant knowledge of French, 12-year-old Kaldor was dumped in a class of four-year-olds, a situation he objected to loudly. “My mother agreed it wasn’t very satisfactory and said, ‘Fine, you don’t have to go but I’ll take you to every museum and monument in Paris, because we may never come back’.

“We were really in limbo, stateless, and didn’t know where we’d end up – maybe Latin America, Canada, Australia or New Zealand. My parents applied to all of those countries,” Kaldor says in his gentle, lightly accented voice.

Kaldor accompanied his mother to the famous Parisian museums – the Louvre, the Rodin Museum, the then-Museum of Modern Art and the Musee Marmottan – and soon began venturing out on his own to visit and revisit his favourite artworks, a recreation of sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s studio chief among them. “I absolutely loved it, I was fascinated,” Kaldor says. “Seeing an artist studio recreated with tools, unfinished works – you could almost feel the presence of the artist.

“I really think it had a pivotal influence.”

After four months in France the family emigrated to Australia, arriving in Sydney in July 1949. His parents established an Australian outpost of London-based Sekers Fabrics, and sent Kaldor to St Ignatius College Riverview, a Jesuit-run private boys’ school where he was the first international boarder. Fellow students made fun of his rudimentary English and regularly threw food at him, which led Kaldor to stage a hunger strike in an attempt to convince his parents to send him as a day boy instead. It worked, and life improved immediately.

After school, on the advice and sponsorship of his godfather and parents’ business partner, Sir Nicholas Sekers, Kaldor attended the best design school in Switzerland. Under the tutelage of polymath and prominent Bauhaus teacher Johannes Itten, Kaldor honed his understanding of textiles and combined it with his knowledge of art and design.

After an apprenticeship at Seker Fabrics in England, Kaldor returned to Australia in 1957 to work for Italian emigre Claude Alcorso and his arts-textile company in Hobart. A year later Alcorso would open Moorilla Estate, the vineyard that now houses David Walsh’s Museum of Old and New Art (Mona), and a decade after that found Sheridan, today known for its towels and bed linens.

“Hobart after Europe was fairly simplistic,” Kaldor says. “You could get all sorts of bread, so long as it was white and sliced; and all sorts of cheese so long as it was sliced Kraft.

“[Alcorso] was a great, enthusiastic boss who was interested in art, collected art, and his home, built by Sir Roy Grounds, now forms the entrance to Mona. [He] showed me how a person can combine business, art and culture.”

Within two years Kaldor joined his parents’ textile business on the mainland, which put him on the path to a fateful meeting in 1968, at the Soho apartment of sought-after young artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

Kaldor had travelled to New York to convince the couple to give a lecture and perhaps host an exhibition for Dunlop subsidiary Universal Textiles (the company that by then owned Sekers Fabrics).

“Christo said, ‘I can’t lecture, my English isn’t good enough and I don’t want to do an exhibition’,” Kaldor recalls. “‘Can you find me a coastline to wrap?’”

The artists had previously tried and failed to gain permission to temporarily wrap coastlines in California and the south of France and recognised Australia offered one of the world’s longest stretches of coast.

“You don’t get asked every day to find a coastline. But I took that seriously and it literally changed my life,” Kaldor says.

Kaldor found a 2.5-kilometre stretch of shoreline at the old Prince Henry Hospital site in Little Bay, and convinced the hospital’s CEO to allow two avant-garde artists to come and wrap the land in fabric. What followed was an extraordinary effort of time, energy and chutzpah, not least by Kaldor, who had to raise funding – some from Dunlop, some from selling Christo’s previous works – plus material contributions from rope and fabric suppliers.

Over many months 100 volunteers devoted 17,000 hours to wrapping the coastline – some sections 26 metres high – using 93,000 square metres of fabric, 56 kilometres of rope and 25,000 Ramset fasteners.

“Nobody wore safety gear; no ropes. Luckily the gods were smiling on us because nobody got hurt,” Kaldor says incredulously. “A few years ago we did a project with German artist Gregor Schneider and I was at Little Bay looking at those rocks and thought, ‘John, you must have been out of your mind’.”

After Wrapped Coast Kaldor started his own business, John Kaldor Fabricmaker, which allowed him to bring ground-breaking public arts projects – featuring international artists – to Australia. He travelled up to 11 months a year, which helped him discover new artists and make the kind of connections that saw him serve on the boards and advisory councils of London’s Tate Modern and New York’s MoMA PS1. (He’s currently a member of MoMA’s International Council.) Half a century on, Kaldor continues to discover and offer access to art that challenges and enlightens us in unexpected ways.

Australia is fortunate to have many dedicated arts patrons, the NGA’s Hart says, but “the way John has done it is quite distinctive, and he laid the groundwork for people who came later.

“His KPAP projects shouldn’t be seen in isolation. He’s gone into the education space, he’s made gifts to galleries. You can look at other patrons who have done things in some of the spaces John’s worked in but it’s the combination – the sum of the parts – that makes him different.”

In addition to decades of free exhibitions, Kaldor has made significant personal donations – often with his wife, fellow arts patron, philanthropist and influential businesswoman Naomi Milgrom – to numerous Australian arts institutions including but not limited to the NGA, MCA, NGV and most notably the AGNSW. In 2011, Kaldor gifted his personal collection (valued at $35 million at the time) to the state gallery.

A public education program has also accompanied each KPAP project since 2011, and something Kaldor’s most proud of is that various projects from the past 50 years are now taught in the HSC syllabus.

In the case of one of KPAP’s two 50th-anniversary projects, the artwork came direct to Kaldor. Wrapped Coast had such an effect on two residents of Little Bay in the 1960s that 50 years later, they started The Living Archives Project to celebrate the anniversary with the local community. Randwick Council agreed to collaborate, and sent a mail-out to residents asking for their recollections of the project. Various memories, phone calls, emails, even bits of fabric and rope have been turning up at the Kaldor offices ever since.

“That’s really going to the heart of our projects,” Kaldor says. “Because they’re all temporary we’re looking for the public memories, the collective memory, if they live on they can only live on in the memory of people.”

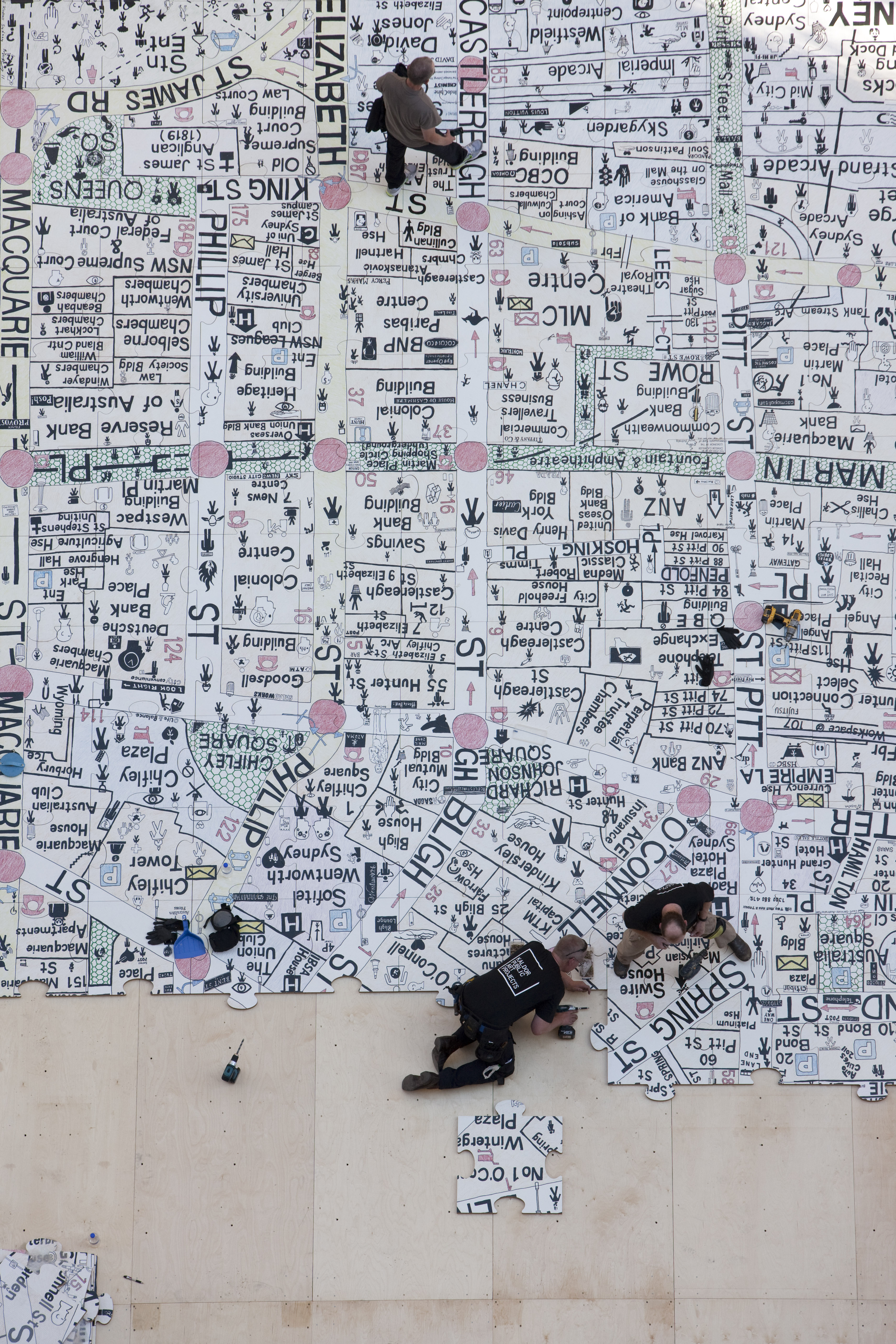

The other commemorative project is Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects, a collaboration with the AGNSW and British artist Michael Landy, whose 2011 KPAP project, Acts of Kindness, proved a hit with the public. Landy asked the community to nominate random thoughtful gestures it had observed in the local area, which he then mapped on the ground at Martin Place.

Landy, Kaldor and Chambers will present photographs, films and artworks from the KPAP archives, which Landy will also collate into a billboard-sized drawing greeting visitors, constituting the 35th installation from KPAP. A number of local artists have been commissioned to respond to the works, including Imants Tillers, an award-winning Australian visual artist who switched from studying architecture to art after helping out on Wrapped Coast, and young Australian multimedia artist Agatha Gothe-Snape.

Kaldor’s excited to continue collaborating with Australian artists, especially following the rich experience Indigenous artist Jonathan Jones’s 2016 work barrangal dyara (skin and bones) gave him and the public. The vast sculptural installation, KPAP’s 32nd project, occupied 20,000 square metres of the Royal Botanic Gardens and recreated one of the city’s most traumatic – but largely unknown – events. Garden Palace, a building three times the size of Sydney’s QVB, burnt to the ground in 1882 and with it irreplaceable Indigenous artefacts.

“That was such an eye opener,” Kaldor says. “Jonathan opened my eyes to a completely different history and a completely different world.

“Art can open people’s ideas to another dimension.”

Making Art Public: 50 years of Kaldor Public Art Projects runs at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from September 7, 2019 to February 16, 2020. Entry is free.