Dust-diffused sunrays stream onto rows of retro sewing machines, rusted and probably dysfunctional, but brought to life by an orchestra blaring from within. Installed in each machine is a speaker, and every one pierces the room with the sounds of its own instrument. As I wander among them, tuning into their differences, I’m overwhelmed by what feels like grief – or is it awe? I can’t quite tell, but that’s what acclaimed street artist Tyrone “Rone” Wright invites you to work out for yourself.

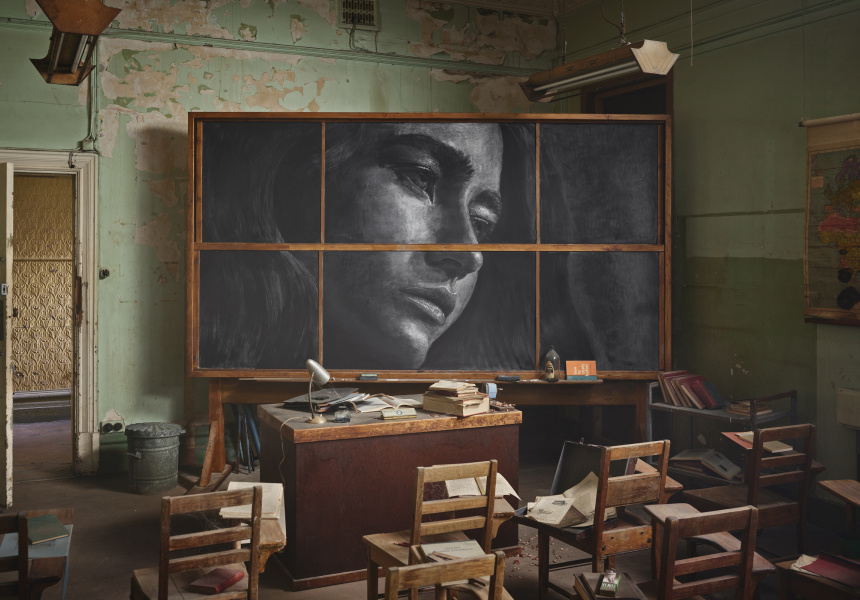

Three years ago, Rone transformed a dilapidated Dandenong Ranges mansion into an overwhelming immersive exhibition, Empire. Now, he’s reimagined another majestic Victorian building – and interpreted the stories hidden in its walls. Across 11 rooms on the third level of Flinders Street Station, the blockbuster new installation, Time, is a journey through the typing pools, machine rooms and public libraries of mid-century Melbourne. Each room is guarded by Rone’s signature towering, ghost-like portraits – a phantasmagoria of Melbourne’s history and mystery.

Is there a more fitting location for Time than Flinders Street Station’s eerie, long-abandoned ballroom – and hidden floor? We rediscovered the space last year when Patricia Piccinini’s fantastical A Miracle Constantly Repeated took it over. But Rone has made it marvellously unrecognisable – it’s now a sprawling attic where you can rummage through the remnants of post-World War II Melbourne.

We think you might like Access. For $12 a month, join our membership program to stay in the know.

SIGN UPHe calls the space his “white whale”. And it took years of persistence – bombarding the right inboxes – to finally conquer it, one of the city’s most iconic structures. “I basically just kept hassling until someone gave up,” Rone tells Broadsheet. “This whole project started three years ago. I saw it in late 2019 and discovered there’s so much more than just the ballroom space up here. It’s quite a beautiful old government administration building. But also, it was a community hub.”

Since its completion around 1910, the station’s upper level has played host to countless fabled functions, which is partly what appealed to Rone’s imagination. “My work is often trying to respond to the space or the architecture,” he says, “but in a way that feels like it’s always been there, that helps me kind of tell that story of something frozen in time and forgotten.” His eclectic interpretation of the disused space includes a paper-sprawled mail room, an intimidating director’s office and a pharmacy with shelves full of dusty bottles – all inspired by the workers, many of them migrants, that helped shape modern Melbourne. And all the rooms abandoned, as if in the middle of the work day.

But moving through each room, it’s clear Rone also has a decided disinterest in realism: there’s a Hogwarts-ian library with spiral staircases, an imposing glasshouse crawling with ivy and a clocktower drawing on the station’s distinct clock-covered facade.

Rone and I stand alone in the dead-silent library. Despite it being a bright spring afternoon, little sunlight peers through the sheer curtains. In here, it looks like day is only about to break, and you’ve lost track of time tiptoeing around the library after hours. But chairs have been flipped sideways, blanketed by tossed books. A discreet door reveals a secret room. And a battered glass display cabinet is pseudo-preserving treasures and historic documents. It sits under the wistful watch of an ethereal, ceiling-high portrait of a woman. “[It’s] my signature thing,” Rone says. “But once the sounds start and the lights go on, it’s like walking through a movie.”

At the press of a button, a cinematic symphony bleeds out from all corners of the room, almost swallowing us up. Composer Nick Batterham remotely conducted the soundscape with the Budapest Orchestra, so when Rone summons it with a small green button on his iPad, I can’t help but think how at odds it is with the scene in front of us.

But it’s just one piece of a ginormous puzzle. Rone and his team (about 120 Victorians have hands in the project) have been piecing it all together on-site since July. Everything you see has been squeezed through an 80-centimetre-wide door, requiring set experts Carly Spooner and Callum Preston to really lean on their team’s flat-packing prowess.

Even before its opening, Time’s season has been extended to April next year, at which point all the sets will be deconstructed and all the murals will be destroyed (they’re painted onto layers of rice paper that leave minimal impact on the heritage walls). A pop-up print shop on the second floor will be among the only evidence of the exhibition that remains.

But there’s not so much as a hint of sadness in Rone’s voice when I ask about his murals’ fate. “There’s a feeling or story that usually only I have [about] my work on the street. But now, people will come in and have a personal connection to it,” he says. “Now, they also grieve its loss, and it kind of helps highlight the fragility of what street art and graffiti is. They have that realisation that this is an enjoy-it-while-it-lasts kind of thing.”

Time opens tomorrow, Friday October 28, at Flinders Street Station Ballroom, and runs until April 2023. Tickets are available online.